Last week's damning report by the thinktank the Institute for Government, which called for a slowdown in the government's privatisation of public services, showed yet again how difficult it is to take private sector models and simply apply them wholesale to public managers.

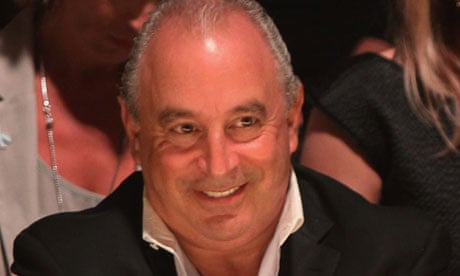

It is a mistake that this government has made time and again. In 2010, Topshop boss Sir Philip Green was asked to review the efficiency of government spending. His approach was clear. "There is no reason," he wrote in the resulting report, "why the thinking in the public sector should be different from the private sector."

Much of the advice that flows from the private sector to the public sector seems to take a similar point of view by seeking to impose private sector approaches in the public sector. But this is not a good starting point.

In reality, there are plenty of reasons that managers in the private and public sectors must think differently, and it is important to understand these differences before dispensing or receiving advice.

Two factors stand out. The first is the absence in the public sector of a single, straightforward way to measure success.

In private firms, almost every decision can be framed by asking: "Will this make us more or less profitable?" Local government and NHS managers have no such luxurious simplicity. Public services usually have multiple objectives, which may include making society happier, safer, freer, wealthier or fairer. And even if you define these objectives, it can be hard to come up with a concrete measure for concepts as nebulous as happiness or fairness.

This lack of a simple way to measure success can make the most fundamental management tasks – devising a strategy, setting targets, motivating people, assessing performance – much harder.

Green's task was a good example. It is tempting for the private sector to consider government spending mainly from a cost point of view, but, in fact, the government needs to consider how it can use its buying power to achieve all sorts of different objectives, which might range from helping to regenerate poor areas to building capacity in new industries.

The second factor is democratic accountability. Consider how Green's life would change overnight if his main business, Arcadia, became democratically accountable. He would suddenly have a shadow opposition board seeking to undermine him as loudly as possible at every turn. And every decision, expense, performance metric, contract, recruitment process and procurement would be liable to public scrutiny – and the scrutiny would typically be challenging, negative and, at times, wilfully unfair. From a management perspective, working under this constraint makes administration inevitably unwieldy. In maths parlance, public sector managers need to "show their workings" while trying to deliver quickly and effectively – no easy task. More insidiously, this constraint can make it harder to innovate and take risks. The rewards for getting it right are not as large as the penalties for getting it wrong.

New York mayor Michael Bloomberg told me: "In business you do things away from the scrutiny of the public. Sometimes you don't even have to tell your own employees. In government … the first thing you think about is how to communicate what you're doing and what the press will say. If you try something new and it doesn't work, the word 'failure' is in the headline."

There are other differences. Few private sector managers have experience of working at the scale and complexity found in the public sector; the latter typically manage demand rather than create it, and, of course, they must work with politicians.

This does not mean managing directors of private companies are incapable of offering useful advice to their public sector counterparts but, given the distinct and more complex challenges faced by the latter, it means that, if anything, public managers should be offering advice to the private sector more often than the other way around.